published in Environmental Science and Technology (open access), DOI: 10.1021/es501998e, Supporting Information here.

A formal version of the FAQ is also available at the website of the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. A blog post with a brief description of the main conclusions is here.

General

1. What are the objectives of this survey?

The PBL aimed to characterize the spectrum of scientific opinion about physical climate science issues. The research was focused on issues that are a frequent topic of public debate, and explored questions such as:

- On which issues is there widespread agreement amongst scientists?

- On which issues do scientists hold varied opinions?

- How does the spectrum of scientific opinion compare to IPCC assessments?

- How do scientists view skeptical arguments and viewpoints?

2. What is the relevance of an opinion survey or of measurement of consensus in trying to assess the science?

Science is based on the critical evaluation of available evidence in the context of existing knowledge. It is not “just an opinion.” With this survey, we tried to identify how scientists assess the different viewpoints that exist in public discussions of climate science. If the evidence for a certain viewpoint has become sufficiently strong and stable over time, the scientists’ aggregated opinion could be expected to reflect that.

3. Are the survey results publicly available?

The full survey results are not publicly available, because the PBL intends to use the data for further analyses.

Update:

Graphs with the ‘straight counts’ for every question (i.e. the number of responses for each answer option) are available in a background report. These results are not segregated in different sub-groups.

Conclusions

4. How does this study compare to the often-quoted 97% consensus?

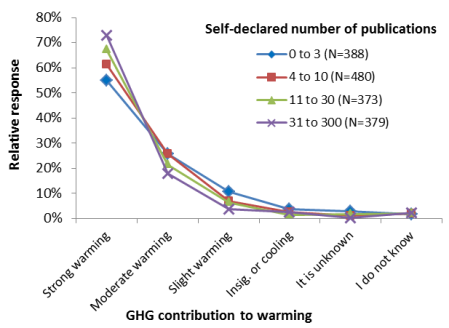

Our results are consistent with similar studies, which all find high levels of consensus among scientists, especially among scientists who publish more often in the peer-reviewed climate literature.

Cook et al. (2013) found that 97% of papers that characterized the cause of recent warming indicated that it is due to human activities. (John Cook, the lead author of that analysis, is co-author on this current article.) Similarly, a randomized literature review found zero papers that called human-induced climate change into question (Oreskes, 2004).

Other studies surveyed scientists themselves. For instance, Doran and Kendall-Zimmermann (2009) found lower levels of consensus for a wider group of earth scientists (82% consensus) as compared to actively publishing climatologists (97% consensus) on the question of whether or not human activity is a “significant contributor” to climate change. Our results are also in line with those of e.g. Bray and von Storch (2008) and Lichter (2007).

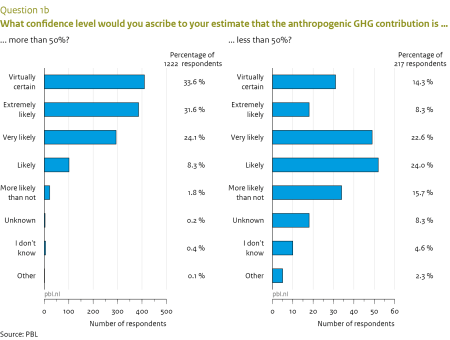

In our study, among respondents with more than 10 peer-reviewed publications (half of total respondents), 90% agree that greenhouse gases are the largest – or tied for largest – contributor to recent warming. The level of agreement is ~85% for all respondents.

While these findings are consistent with other surveys, several factors could explain the slight differences we found:

- Surveys like ours focus on opinions of individual scientists, whereas in a literature analyses the statements in individual abstracts are tallied. Literature analyses have generally found higher levels of consensus than opinion surveys, since the consensus is stronger amongst more heavily published scientists.

- This study sets a more specific and arguably higher standard for what constitutes the consensus position than other studies. For instance, Doran and Kendall-Zimmermann (2009) asked about human activity being a “significant contributor” to global warming, and Anderegg et al. (2010) investigated signatories of public statements, while we asked specifically about the degree to which greenhouse gases are contributing to climate change in comparison with other potential factors.

- Contrarian viewpoints are somewhat overrepresented in our survey and they may have overestimated their self-declared level of expertise (see question 9).

5. How is the consensus or agreement position defined?

The consensus position was defined in two ways:

- Greenhouse gases contributed more than 50% to global warming since the mid-20th (Question 1). This is analogous to what was written in IPCC AR4.

- Greenhouse gases have caused strong or moderate warming since pre-industrial times (Question 3). “Moderate” warming was only interpreted as the consensus position if no other factor was deemed to have caused “strong” warming. This response means that greenhouse gases were considered the strongest –or tied for strongest- contributor to global warming.

The former definition exactly mirrors the main attribution statement in IPCC AR4 and served as a ‘calibration’ for the latter.

6. What does “relative response” mean on the y-axis of many Figures?

This gives the percentage of the respondents (often within a certain sub-group) for the specific answer option. We opted to show the relative response rather than the absolute response to enable comparing the responses of different sub-groups (with differing group sizes as denoted by N=…) within one graph.

7. What are “undetermined” answers?

Those are the sum of responses “I don’t know”, “unknown” and “other”.

8. Why do IPCC AR4 authors show a higher consensus than the other respondents?

AR4 authors are generally domain experts, whereas the survey respondents at large comprise a very broad group of scholars, including for example scientists studying climate impacts or mitigation. Hence we consider this to be an extension of the observation -in this study and in e.g. Anderegg et al. (2010) and Doran and Kendall-Zimmermann (2009) – that the more expert scientists report stronger agreement with the IPCC position. Moreover, on the question of how likely the greenhouse contribution exceeded 50%, many respondents provided a stronger statement than was made in AR4. Using a smaller sample of scientists, Bray (2010) found no difference in level of consensus between IPCC authors and non-authors.

9. How reliable are the responses regarding the respondent’s area of expertise and number of peer-reviewed publications?

Respondents were tagged with expertise fields, though these were in many cases limited and not meant to be exhaustive. These tags were mainly used to ensure that the group of respondents was representative of the group that the survey was sent to. A subset of respondents was also tagged with a Google Scholar metric. Those who were tagged as “unconvinced” reported more expertise fields than the total group of respondents and also a higher number of publications compared to their Google Scholar metrics, if available (see Supplemental Information).

10. Since most scientists agree with the mainstream and therefore most media coverage is mainstream, what is the problem with “false balance”?

Scientists with dissenting opinions report receiving more media attention than those with mainstream opinions. This results in a skewed picture of the spectrum of scientific opinion. Whether that is problematic is in the eye of the beholder, but it may partly explain why public understanding lags behind scientific discourse (e.g. the “consensus gap”).

Survey Respondents

11. How many responses did you get to the survey?

Out of 6550 people contacted, 1868 filled out the survey (either in part or in full).

12. How did you compile the list of people to be surveyed?

Respondents were selected based on

- keyword search in peer-reviewed publications (“global climate change” and “global warming”)

- recent climate literature (various sources)

- highly cited climate scientists (as listed by Jim Prall)

- public criticisms of mainstream climate science (as listed by Jim Prall)

13. Are all of the survey invitees climate scientists?

The vast majority of invitees are scientists who published peer-reviewed articles about some aspect of climate change (this could be climate science, climate impacts, mitigation, etc.). Not all of them necessarily see themselves as climate scientists.

14. Why did you invite non-scientist skeptics to take part in the survey?

They were included in the survey to ensure that the main criticisms of climate science would be included. They constitute less then 5% of the survey respondents. Viewpoints that run counter to the prevailing consensus are therefore somewhat magnified in our results.

15. How representative are the survey responses of the “scientific opinion”?

It’s difficult to ascertain the extent to which our sample is representative, especially because the target group is heterogeneous and hard to define. We have chosen to survey the wider scientific field that works on climate change issues. Due to the criteria we used and the number of people invited we are confident that our results are indeed representative of this wider scientific field studying various aspects of global warming. We checked that those who responded to the survey were representative of the larger group of invitees by using various pieces of meta-information.

16. Did you take into account varying levels of expertise of respondents?

Respondent were asked to list their area(s) of expertise and their number of peer-reviewed publications. These and other attributes were used to interpret differences in responses.

17. How did you prevent respondents from manipulating the survey results, e.g. by answering multiple times?

An automatically generated, user specific token ensured that respondents could only respond once.

18. How did you ensure respondent anonymity?

Survey responses were analyzed by reference to a random identification number.

Survey Questions

19. Are the survey questions public?

Yes, survey questions and answer options are available on the PBL website and as Supporting Information (part 2) to the article.

20. How did you decide on the questions to ask?

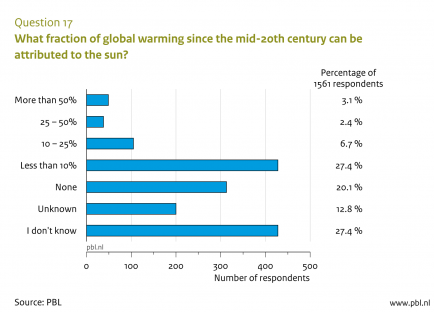

The survey questions are related to physical science issues which are a frequent topic of public debate about climate change.

21. Was the survey reviewed before it was sent to respondents?

Yes, before executing the survey it has been extensively tested and commented on by various climate scientists, social scientists and science communicators with varying opinions, to ensure that questions were both clear and unbiased. Respondents were not steered to certain answers.

——-

Reference: Bart Verheggen, Bart Strengers, John Cook, Rob van Dorland, Kees Vringer, Jeroen Peters, Hans Visser, and Leo Meyer, Scientists’ Views about Attribution of Global Warming, Environmental Science and Technology, 2014. DOI: 10.1021/es501998e. Supporting Information available here.

Please keep discussions on this thread limited to what is mentioned in this FAQ and to other questions you may have about the survey or the article. Discussion of the survey results should be directed at the more generic blog post.