Rowan Sutton just published a very short article (an “idea”) in ESDD entitled “a simple proposal to improve the contribution of IPCC WG1 to the assessment and communication of climate change risks”. From a risk management point of view a focus solely on the most likely outcome is not recommended, especially when the impacts increase sharply towards one end of the scale.

Sutton:

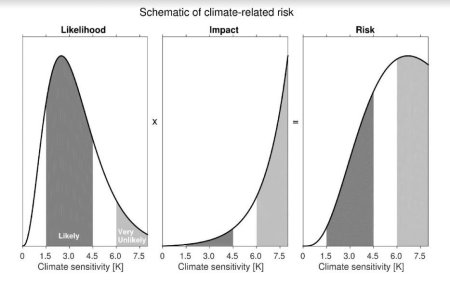

A common measure of risk is likelihood x impact (Fig 1). It is standard practice in risk assessment to highlight both the most likely impacts and low likelihood high impact scenarios. Such scenarios merit specific attention because the associated costs can be extremely high, so decision makers need to know about them. It follows that WGI has a responsibility to assess and communicate explicitly the scientific evidence concerning potential high impact scenarios, even when the likelihood of occurrence is assessed to be small. In past reports the assessment of key parameters by WG1 has focussed overwhelmingly on likely ranges only. When information has been provided about the tails of distributions only likelihoods have been communicated using terms – following the IPCC’s uncertainty guidance (Mastrandrea et al, 2010) – such as “very unlikely” or “extremely unlikely”: a clear steer that policy makers should largely ignore such possibilities. But this is wrong. Policy makers care about risk not likelihood alone. The IPCC’s uncertainty guidance ignores impact and is symmetric with respect to high or low impact scenarios; this is inappropriate for the communication of risk (Fig 1).

Figure 1: A schematic representation of how climate change risk depends on equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS).

Some will argue that the WGII report is needed to provide information on impacts. For detailed information this is certainly the case, but the general shape of the damage function for a large basket of impacts (Fig 1) is insensitive to such details, and is all that is needed to justify WGI providing a much more thorough assessment of relevant scenarios. Other critics will suggest that for WGI to identify high impact scenarios explicitly would constitute scaremongering; this concern is no doubt one reason why previous WGI reports have focused so much on the likely range. But it is misguided. Policy makers need to know about high impact scenarios and WGI has a responsibility to contribute its considerable expertise to making the appropriate assessments.

A very similar point has been made by Kerry Emanuel in his post “Tail risk vs Alarmism” on CCNF:

In assessing the event risk component of climate change, we have, I would argue, a strong professional obligation to estimate and portray the entire probability distribution to the best of our ability. This means talking not just about the most probable middle of the distribution, but also the lower probability high-end risk tail, because the outcome function is very high there.

(…)

But there are strong cultural biases running against any discussion of this kind of tail risk, at least in the realm of climate science. The legitimate fear that the public will interpret any discussion whatsoever of tail risk as a deliberate attempt to scare people into action, or to achieve some other ulterior or nefarious goal, is enough to make almost all scientists shy away from any talk of tail risk and stick to the safe high ground of the middle of the probability distribution. The accusation of “alarmism” is quite effective in making scientists skittish in conveying tail risk, and talking about the tail of the distribution is a sure recipe to be so labelled.

Hans Custers schreef een kort Nederlandstalig blog over Sutton’s artikel.