Dr. Eric Wolff is spot on (see also further below):

as an outsider to the blogosphere, it surprises me that so many people, presumably mostly with even less knowledge and training than me, seem absolutely convinced they have mastered every area of climate science.

A peculiar line-up of speakers assembled recently at the Conference on the Science and Economics of Climate Change in Cambridge: Phil Jones, Andrew Watson, John Mitchell, Michael Lockwood, Henrik Svensmark, Nils-Axel Morner, Ian Plimer, Vaclav Klaus and Nigel Lawson. Bishop Hill reports that

Dr Eric Wolff of the British Antarctic Survey tried valiantly to find a measure of agreement between the two sides.

This proved an interesting exercise and resulted in a useful list (also reproduced by Judith Curry) on what we can all agree on (perhaps excluding those too far out on the fringes; links added by me):

- CO2 does absorb infrared radiation

- The greenhouse effect (however badly named) does occur in practice: our planet and the others with an atmosphere are warmer than they would be because of the presence of water vapour and CO2.

- The greenhouse effect does not saturate with increasing CO2

- The CO2 concentration in the atmosphere has risen significantly over the last 200 years

- This is because of anthropogenic emissions (fossil fuels, cement production, forest clearance). [Ian Plimer disagreed, but as Curry stated: “the anthropogenic contribution is (should be) undisputed”]

- If we agree all these statements above, we must expect at least some warming. [Bishop Hill noted “broad agreement” with this point]

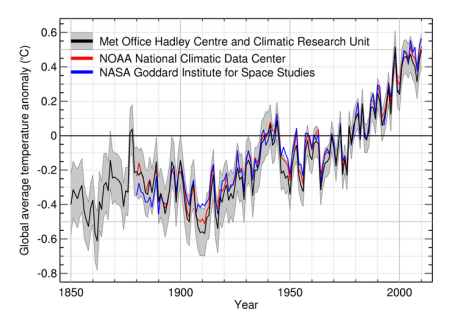

- The climate has warmed over the last 50 years, [as is evident from] land atmospheric temperature, marine atmospheric temperature, sea surface temperature, and (from Prof Svensmark) ocean heat content, all with a rising trend.

- We probably don’t agree on what has caused the warming up to now, but it seemed that Prof Lockwood and Svensmark actually agreed it was not due to solar changes, because although they disagreed on how much of the variability in the climate records is solar, they both showed solar records without a rising trend in the late 20th century. [Excellent point and ironically hitting Svensmark with a stick of his own making. Note the distinction between variability and trend.]

- On sea level, I said that I had a problem in the context of the day, because this was the first time I had ever been in a room where someone had claimed (as Prof Morner did) that sea level has not been rising in recent decades at all. I therefore can’t claim we agreed, only that this was a very unusual room. However, I suggested that we can agree that, IF it warms, sea level will rise, since ice definitely melts on warming, and the density of seawater definitely drops as you warm it.

- Finally we come to where the real uncertainties between scientists lie, about the strength of the feedbacks on warming induced by CO2 [i.e. climate sensitivity]

Eric Wolff also chimed in with a substantial comment over at Bishop Hill’s, rebutting some commonly heard arguments and making some very spot-on remarks:

(…)

I should first state the rationale for the summary I made at the Downing event. The meeting was about the science and economics of climate change, and I was asked to lead a discussion that came between the science talks and the two economics talks. I therefore felt the most useful thing I could do was to try to summarise what we had heard, as a basis for the discussion of whether society should do anything in response to that, and if so what. In particular I did hear a surprising number of things on which almost everyone in the room could agree, and it seemed worth emphasising that, rather than rehearsing old arguments.

I notice in the thread here several comments about who sets the “terms of the debate”, and about the “context of the debate”. While such phrasings may make sense in discussing energy policy, it is a strange way to discuss the science. Our context is the laws of physics and our observations of the Earth in action; our aim as scientists is to find out how the Earth works: this is not a matter of debate but of evidence. I think some of the comments on this blog come dangerously close to suggesting that we should first decide our energy policy, and then tell the Earth how to behave in response to it.

Regarding Plimer’s proposal that volcanic emissions were more important than we thought, (…) if volcanoes were “causing” the recent increase, then around 1800 their emissions would have had to rise above their stable long-term rate, and then stayed high. This is however a rather hypothetical discussion because the change in the isotopic composition of CO2 in the atmosphere over the industrial period is not consistent with an increased volcanic source anyway.

Regarding the idea that the “temperature increase stopped in 2000”: my point is that we know there are natural variations (due eg to El Nino) that cause runs of a few years of temperature colder than the average or a few years warmer. Look on the record at the decade around 1910 for example when there was a long run of cold years on a flat background.

Such a period superimposed on a trend would look like the last decade (but more so). The point of my analogy is that you can’t determine the trend over several months by measuring the gradient in a run of a few days. Similarly, you simply can’t determine a multidecadal trend by measuring the gradient over a few years because all you get is the “noise” of natural variability.

Professor Morner claims that globally sea level has not risen at all; he dismisses the evidence, from both satellites and the global tide gauge network, that it has. (…) There are numerous reasons why a single site can show a sea level signal, either real or apparent, that departs from the global mean.

I am not the best person to discuss models and feedbacks in detail (see comment on expertise below). However, I could not let two issues pass. Firstly, when models are run out for a century into the future, they do indeed show runs of years with flat temperatures amidst a trend (…) (because of El Nino and other natural factors). I am therefore not clear why this is evidence that something is missing. Regarding positive feedbacks: a positive feedback implies amplification, but not a system out of control; this is only the case if the sum of the gain factors is greater than 1.

Finally, a few specific issues that interested or worried me.

(…) CO2 emits infrared as well as absorbing it. (…) indeed, this property is precisely why its effects do not saturate (but fall logarithmically), because it allows the height from which the emitted radiation finally escapes to rise into regions with less and less air.

Geckko accidentally made an important point. S/he did not like the statement: “We can agree that if it warms the sea level will rise”, because it was too simplistic. Well, as a scientist I always like to boil things down to a statement that my brain can grasp, but that contains the essential explanation of an observation or process. And this one does, for example being demonstrably what was observed in going from a cold ice age world, with sea level 120 metres below the present level, to the present. However, you are right: there are factors that could make this statement false, such as increased snowfall when it warms, adding more ice into ice sheets. As soon as several such competing processes have to be taken into account, our brains cannot predict the outcome, and so we have to resort to putting all the “millions of assumptions” into a numerical model and seeing which of them “win”. An argument for models?

Coldish made a good point about expertise, and this is where I am going to go into a slightly more challenging area. I freely admit that I am not an expert on all, or even most, aspects of climate. When I reach a topic that I have not previously studied, I go to those who are experts, either in person or by reading their work. I maintain scepticism about some of their conclusions, but my working assumption is that they are intelligent and that they have probably thought of most of the issues that I will come up with. Can I observe as an outsider to the blogosphere, that it surprises me that so many people, presumably mostly with even less knowledge and training than me, seem absolutely convinced they have mastered every area of climate science.

and more so, convinced that they are right and almost all of the experts are wrong. That must be the height of hubris.

However, Coldish specifically mentioned IPCC, and I think there is also an interesting point to make about that. At the Downing event, there seemed to be two IPCCs in the room. To some it was a huge plot, masterminded by some mysterious power that manipulates troublesome scientists. To me and the scientists in the room, it is (at least in WG1) simply a set of well-researched review papers, describing the present state of the peer-reviewed literature. I mention this only because I think the former view is a type of groupthink where, because people form an extreme opinion in their private space, they think it is widely held, or even true.

Alas, Wolff’s forray into the blogosphere was short, as is evident from a short comment a while later:

Just in case anyone thinks they are addressing me with their remarks:

I thought this might indeed be a chance for a civilised discussion, and some of the respondents seem happy to have that. However there are also a lot of remarks on here that are frankly rude and aggressive, and I won’t be returning. Now I remember why I hate the blogosphere.

Tags: Andrew Watson, Bishop Hill, climate sensitivity, Eric Wolff, global average temperature, greenhouse effect, Henrik Svensmark, Ian Plimer, John Mitchell, Michael Lockwood, Nigel Lawson, Nils Axel Morner, Phil Jones, saturation, sea level rise, temperature trend, Vaclav Klaus, Venus, volcanic emissions

May 25, 2011 at 20:28

I am still stunned by the ability of Plimer to deny the anthropogenic origin of CO2, and for Morner to deny the increase of global sea level. Or maybe, I’m stunned that people who can deny basic facts like that still get listened to.

May 25, 2011 at 20:50

Nice post Bart, I hadn’t heard about any of this. Wolff clearly has had little exposure to “skeptic” blogs :-)

What a bizarre lineup of speakers. Jones, Morner, and Klaus? It would have been a fascinating conference to watch, at least. As M notes in the comment above, at least Morner and Plimer were the only ones denying indisputable facts, but it’s still hard to believe that anyone would take either of these two seriously, no matter how strong their denial. Good job by Dr. Wolff to get the “skeptics” to agree on most indisputable facts, which many “skeptics” continue to deny.

May 25, 2011 at 20:55

True, M. I was quite stunned a while ago when an acquaintance with a long career in atmospheric chemistry claimed that volcanoes emit more CO2 than humans. He was deaf to hearing that that isn’t the case by a large margin. Guess at some point such convictions become part of your identity. And then there’s no way back. Plimer, Morner and many more like them are clearly in that stage. Professional deformation comes to mind.

May 25, 2011 at 22:14

Bart: Interestingly, there are some individual volcanoes which are impressive CO2 emitters – Mt. Etna, for example, emits 25 Mt/year, which is more than twice as much as a typical coal plant.

Of course, Mt. Etna is also estimated to be responsible for a whopping 15% of total volcanic emissions each year (http://www.springerlink.com/content/v9ar1lrkc20nvpym/), so the sum total volcanic contribution is, well, puny.

Everyone has some amount of professional deformation, but denial of the anthropogenic origin of CO2 is taking professional deformation to a pathological extent… in some cases I know of, I’d also blame, “going emeritus”.

May 26, 2011 at 04:53

Bart,

What an interesting post, and a refreshing outside perspective by Dr. Eric Wolff.

It may be valuable to gain the insights of someone like Eric Wolff, who is blissfully unaware of the tribalism and repetitive arguing rampant on both ‘alarmist’ and ‘denialist’ blogs.

His credo of NOT framing the questions according to political, blogotribal or ideological preference but in accordance with: “Our context is the laws of physics and our observations of the Earth in action; our aim as scientists is to find out how the Earth works: this is not a matter of debate but of evidence.” is right on the mark.

This leaves me wondering whether we haven’t lost a lot of professionalism, and a sober perspective, by moving into the blogosphere. The format, and the instantly available option to argue and to impress our views upon others may just prove to be a distraction.

May 26, 2011 at 05:58

Hi Bart,

I would be in agreement with what Dr. Wolff wrote above. Moreover, I’m pretty sure that people ranging from Anthony Watts to Steve McIntyre would, too.

I think the problem arises from the fact that lukewarmers and skeptics think that what is presented as the ‘minimum consideration set’ is also pretty close to the maximum extent of our knowledge. And I think that you and many of your regulars think that our knowledge goes way beyond what is presented by Dr. Wolff.

So I guess we’ll still have something to talk about…

May 26, 2011 at 07:29

Interesting post.

Regarding text in red, see Dunning Kruger Effect.

May 26, 2011 at 08:09

I think Eric Wolff missed a chance there to show how stupid (yes, yes, not very nice to say) it is to think that volcanoes emit more than humans. If that were the case, there should be a sink that is more than three times bigger than the one that keeps only human emissions ‘in check’. Every year. For the last many decades. I wonder what that sink is supposed to be? It would have had to absorb many thousands of gigatons of carbon since the early 19th century!

May 26, 2011 at 09:16

Nothing on paleo (it being the strongest aspect of the case)?

May 26, 2011 at 09:25

Bob,

That passage is right on the mark indeed.

Marco,

Given his already lengthy response, I think Wolff dealt with the volcano issue very satisfactorily (my paraphrasing: isotopic footprint makes such allegations pretty much moot anyway). Moreover, I think it much better to not use words like “stupid” but let the audience come to that conclusion themselves without you spelling it out for them. Calling people names is not a good communication strategy.

Steve,

Good point. My list of important and reasonably well understood points re climate change science (which I’ve wanting to write about for ages) would indeed include paleo.

May 26, 2011 at 11:54

Bart, any word can be considered an insult, regardless of whether it is the appropriate description of someone’s knowledge. Claiming Plimer and Mörner suffer from professional deformation is in that sense an insult, too…

(and it is also an insult to those who trained these people, as if it is their training that causes their inability to accept basic facts).

May 26, 2011 at 13:27

Marco,

True, in the end it’s in the eye of the beholder, but I try to look through their eyes when writing/speaking in public. As a wanna-be psychic so to speak.

May 26, 2011 at 14:09

A point which is often repeated about the intractability of the middle east is that you don’t get to negotiate with your friends, you agree with them. Wollf misses this about blogs. Yes, it is rough out there, but that’s life and you can either retreat to your comfort zone or dig in. What he did was retreat to concern trolling after a masterful exposition

There are strategies to deal with what he met at Hillhouse, ignore it, plowing through with more challenges to your opponents thoughts (Bob Grumbine did a masterful job of this at CA on what is an engineering report. Meet it with ridicule, give as well as you get and so forth. Each style has a role to play

May 26, 2011 at 15:22

Eli writing of style… as I live and breathe.

I have Plimer’s book. It is unreadable and repetitive and really expensive. I don’t have any idea what he is up to.

On the other hand, taking paleo evidence for granted and as the strongest link in the chain seems… well, fraught.

May 26, 2011 at 17:38

Wolff provides a good example of what is, ultimately, the biggest problem we face in achieving meaningful action on climate change:

Rational person gets involved in the debate.

Rational person quickly becomes disgusted by the state of humanity displayed in the debate.

Rational person withdraws from the debate.

Debate remains dominated by irrationality.

This is the intentional (or perhaps just subconsciously but successful) aim of many.

I second Eli’s strategies, but be willing to adapt them as each strategy becomes singled out and targeted.

May 26, 2011 at 21:16

Hi Bart,

Sorry to pursue you over here from Bishop Hill’s blog, but I think my question probably got somewhat lost in the debris back there. Can I try again here, please?

In a similar vein to Tom’s comment above, I observed that as far as an outsider can tell, virtually everyone working in climate science accepts the basic AGW propositions mentioned by Eric Wolff (GHE, human emissions driving C02, warming expected), and of course so do I. I then pointed out that this consensus does not offer very much guidance to policy makers, and that on the critical questions there is a great deal of argument between different groups of researchers. Many of the scientists who question whether the evidence on CO2 demands urgent action are very senior figures, with numerous published papers and years of experience behind them, and it does not seem reasonable to simply ignore their comments.

I’m not myself a climate specialist, so forgive me if I am missing the point somewhere. But I have worked in academic physics research in the past, and to be honest a dispute like this doesn’t strike me as being that unusual at the cutting edge. In this case though, I do think the fact of such a dispute deserves a considered explanation, since it is both so visible to the general public and since so much hinges on the resolution. What is your take on this? Why is there this dispute, and how can it be resolved?

May 26, 2011 at 21:55

Philip,

Interesting and quite involving questions.

I think it’s actually opposite as what you say: The central issues that we know, in a similar vein as mentioned by Wolff but perhaps with some more things added (eg paleo, timescales, effects) are actually what matter politically. The uncertainties much less so in my opinion; they’re merely scientifically interesting but hardly politically relevant. See also some older posts here, eg https://ourchangingclimate.wordpress.com/2008/11/06/herman-daly-on-climate-policy/

On why there’s much disagreement on how to deal with climate change, I think Ropeik over at CaS is spot on:

“the underlying cultural and psychological motivations are the real reasons for THE ARGUMENT.” (about climate change, or anything for that matter)

http://www.collide-a-scape.com/2011/05/25/getting-past-the-argument/

It’s a matter of risk and a matter of how much you care for the future (it’s not OUR problem: https://ourchangingclimate.wordpress.com/2010/09/06/future-generations-global-warming-is-not-our-problem/ and https://ourchangingclimate.wordpress.com/2010/07/21/the-risk-of-postponing-corrective-action/ )

Sorry to send a whole linkfest your way…

May 26, 2011 at 22:37

Allow Eli to add a bit to what Bart said. The central frustration, and you see this in what Eric Wolff and Bart wrote, is that there are those who simply reject the most basic knowledge about climate, Morner and Plimer for two examples, but on a slightly more sophisticated level the Pielkes, Fred Singer, etc. While in the former cases the rejection is direct and clownish, in the later case the rejection of science arises from a worldview that holds that if the scientific underpinnings are accepted that would lead to action being taken which they do no want. That game could be called yes but.

In the face of this studied rejection one cannot even get close to the issues that Phlip is trying to reach

May 26, 2011 at 23:19

I mostly agree with Philip’s comment. There are basic issues we are confident about, as summarized by Wolff (although many deniers like Plimer and Morner deny them). Then there are uncertainties like the aerosol forcing, cloud feedback, overall sensitivity, etc. I wouldn’t necessarily call it “argument between different groups of researchers”, except a select few (Spencer, Christy, Lindzen) who do argue that somehow sensitivity is low. Almost all other climate researchers agree it’s probably somewhere between 2 and 4.5°C for 2xCO2. Uncertainty isn’t the same thing as disagreement.

Philip also says “this consensus does not offer very much guidance to policy makers”. I disagree here. There’s a pretty strong consensus that allowing more than 2°C warming above pre-industrial is too risky. It’s generally agreed upon by both scientists and policymakers (at least those who attend international climate conferences), in fact. And 2°C warming corresponds to a certain amount of carbon emissions. So while climate scientists generally don’t say “you need to implement a carbon tax”, they do say “you need to limit total global CO2 emissions below 1 trillion tons”, or whatever the number is.

But anyway, it’s hard to even get to a policy discussion when the Plimers and Morners of the world are denying the basic facts, and people are actually listening to them.

May 26, 2011 at 23:24

Bart,

Thanks very much for your detailed reply, and no problem at all with the linkfest – all good reading!

To be honest, I’d imagined that the problem for the politicians is that the central issues that we know don’t provide a clear indication of the magnitude of the effects (or if you like, the range is very wide). Hence, although the politicians may think that they need to do something, it is not really clear what that something is. So for example, the issues that we know imply it is wise to reduce CO2 emissions (I think Martin Rees has made this point strongly – and I agree with him). But from this to the need for urgent mitigation seems to require somewhat more, especially given the risks some have identified as inherent in the mitigation policies.

I also agree with the idea that we hold the world in trust for future generations, but this is a double-edged sword that applies as much to the risks of mitigation as it does to the risk of serious consequences of fossil fuel use. By comparison, in the smoking analogy you mentioned there are no risks involved in giving up (although a little pain certainly).

Actually I think we’ve rather skipped around the edges of my question, perhaps because I haven’t expressed myself clearly enough. For example, Ropeik’s comments seem based on the assumption that the conclusions beyond the issues that we know have already been established to a similar level, whereas I was more interested in what is happening now.

To an outsider like myself, the scientific argument looks far more like a normal scientific debate between groups pursuing different research strategies. That the debate involves a significant number of senior scientists on all sides suggests that the argument has not yet been resolved, but of course experience suggests that it will be in due cause as more evidence is produced. Do you think this is fair, or is there a better explanation?

Philip.

May 26, 2011 at 23:53

I should add that while most scientists and policymakers understand the risks involved and what we need to do to address them, the real problem is that a large segment of the population doesn’t. Like in the USA, close to 50% of the population doesn’t even believe we’re causing global warming, let alone dangerous warming that we need to address immediately. And in the end, policymakers answer to that public. And the public gets informed by the media, much of which (particularly the Fox Newses of the world) communicate the positions of the deniers like Plimer and Morner.

May 27, 2011 at 03:32

“To an outsider like myself, the scientific argument looks far more like a normal scientific debate between groups pursuing different research strategies. That the debate involves a significant number of senior scientists on all sides suggests that the argument has not yet been resolved, but of course experience suggests that it will be in due cause as more evidence is produced. Do you think this is fair, or is there a better explanation?”

Yes, I am afraid there is a better explanation. For one thing, you have to be able to assess the nature and calibre of the “senior scientists” involved. Someone may be senior … and anyone near the field would know they had been wrong again and again.

The second thing is that this far more like the tobacco wars, in fact that’s where the delay strategies originated, with John Hill in 1954. The medical science was becoming clear enough, and they had to keep obfuscating it, which they did successfully. Some of the same people, thinktanks and front groups helped tobacco, then shifted to climate.

Read Oreskes and Conway, Merchants of Doubt (2010),for example.

Or, if you want a somewhat orthogonal slide, see my Crescendo to Climategate Cacophony. Sadly, most of this originates in the USA, especially around K-Street in Washington, DC. The theme “more research needed, wait” started around 1990, with a book by the 3 founders of the George Marshall Institute. Much of the strategy for the last 10 years was designed in the 1998 GCSCT meeting hosted by the American Petroleum Institute. (See p.82, you can read their strategy document, which they have been executing. I am afraid science doesn’t do well in the short term versus well-funded, well-organized PR/lobbying. The tobacco guys proved that, and confusing people about climate is child’s play compared to keep addiction children to nicotine. It might be a plus for an individual to stop smoking, but it is a terrible minus for tobacco company profits, as they’ve know for decades.)

But again, please name who you think are the credible senior *climate* scientists who do *not* think AGW is a problem, in 2011? Of course scientists argue around the edges.

May 27, 2011 at 04:57

I would add to Eli’s point that there are also a fair number of people, including some scientists, who are incredulous regarding the idea that reality could do something like this. This is easy to understand in fundamentalist Christians like Christy and Spencer (although of course it’s not the only thing going on since there are plenty of religiously conservative scientists who think otherwise) but more difficult with some others. In addition there are folks who just like being contrarian about things (Lindzen and Dyson e.g.). Both of these groups overlap with the more political variety (which can be divided in turn into those who might be called principled ideologues and those like Fred Singer who have just plain sold out to the highest bidder), which makes it complicated to assign specific motivations to individuals. An enticement to all of these is the propspect of a second career on the denialist rubber chicken circuit.

[edit. No baiting please. BV]

May 27, 2011 at 09:48

Philip,

As lifted from my comment at Lucia’s (Zeke’s commendable post on what we can agree on, along a similar vein as Wolff’s, but wider in scope):

I think the policy relevance of the uncertainties (e.g. what climate sensitivity really is (e.g. 2, 3, 4.5) or whether sea level will rise by 0.5 or 1.5 metres by 2100 under BAU) is very small in the short term, but gets increasingly larger for the longer term. This is because with all likely outcomes, GHG reductions are equally necessary (or unnecessary, dependent on how someone views the nature of the problem). Since no serious measures to reduce emissions globally have been enacted so far, the trajectory of emission reductions will begin the same in all cases. It’s only further down the road, when serious mitigation action has started, that it starts to matter for the optimal policy portfolio what the exact sensitivity or SLR is.

In short: If it’s bad, it’s really bad. If it’s good, it’s still pretty bad. So for the steps to undertake (initially at least), it doesn’t matter much precisely how bad it will be. We’re driving in a snowstorm and it’s advisable to reduce speed. Whether 30 or 60 km/h is the optimal speed is perhaps not certain, but we know that continuing with 120 km/h is not a wise option for the long term.

If someone wants to take the less likely outcomes into account (eg sensitivities below 1 or above 6), the risk actually becomes larger (because both the probability and the cost functions mhave fat tails) rather than smaller. Taking only the best case scenario into account is not rational risk assessment imho.

The vast majority of scientists agree on the basic premise of greenhouse induced warming because the evidence taken together is overwhelming. That is not altered by the fact that there are fierce arguments about the existing uncertainties or that there is a small but very vocal group (amongst whom some ‘very senior ones’ such as Lindzen etc) who proclaim that the basic premise is wrong.

I think the dynamic of the public debate is far removed from a normal scientific debate. If this were a scientific debate about the mating behavior of fruitflies we wouldn’t be having this discussion. It’s precisely because the potentially large societal implications of the science that the debate got so politicized and that people are at a challenge to separate the facts from their own ideological filtering (which is to an extent unavoidable, though by and large scientists are through their training more used to do so. That doesn’t mean though that they’re immune to it; they’re still people of flesh and blood).

May 27, 2011 at 15:19

“There’s a pretty strong consensus that allowing more than 2°C warming above pre-industrial is too risky”

Er. That’s not quite true. I think most climate scientists would agree that risks increase with increasing temperatures, but I think that it is actually a minority that pick a specific number and say “Thou Shalt Not Cross”. 2 degrees C is more a policy and NGO construct than a scientific figure. There are certainly _risks_ involved with 2 degrees C- possibly commitment to a long-term collapse of the Greenland ice sheet, possibly, in combination with acidification, loss of much of our coral reefs, etc. etc. – but it isn’t a scientist’s job to decide what risks society is willing to take. Plus, ideally you’d know how much it would cost society to meet a target.

Now, I am a human being in addition to being a climate scientist, and as such I might have opinions about what a good target would be. Though actually, my opinion is that we shouldn’t obsess so much over the long term target, and instead just get a framework set up for near term reductions that could be tightened over time. I wish I could go back in time and shake the Kyoto negotiators and get them to set up a low price harmonized carbon tax (with some deforestation, developing country aid, and other such provisions) rather than going down the cap & trade route which required countries to pick specific targets from an arbitrary baseline and had built-in large inter-country transfers (eg, hot air to Russia) and so forth… but that’s not my _science_ opinion…

May 27, 2011 at 15:35

Thank you to everyone who has responded to my question, all very informative and much appreciated.

May 27, 2011 at 17:35

Bart – well said.

M – maybe it’s not scientists’ jobs to determine what risks society should take, but that doesn’t mean they’re not allowed to have opinions on the subject. I stand behind my statement – most scientists would agree that causing warming greater than 2°C above pre-industrial is an unacceptable risk.

May 27, 2011 at 19:44

Philip, Bart,

A well-informed discussion, as is usual at Bart’s place. Although I agree with most Bart has brought forward, and pretty much everything said by Eli and by John Mashey, a particular phrase caught my eye:

“.. I was quite stunned a while ago when an acquaintance with a long career in atmospheric chemistry claimed that volcanoes emit more CO2 than humans. He was deaf to hearing that that isn’t the case by a large margin. Guess at some point such convictions become part of your identity. And then there’s no way back.”

This is the main explanation why – as Philip mentioned – some senior scientists may cling to an untenable position, even in the face of mounting evidence.

All the politics and ideology infused into the “climate change debate” just makes this a lot worse. It makes for an ideal platform (as well as an eager audience), for any well-known scientist or emiritus to maintain his fame of old by staking a claim against the majority of climate scientists.

Once their ego is fully inflated… it becomes harder and harder to change their position. It might mean not just a loss of face with their professional colleagues, but now also a loss of their sense of self-worth and the way they perceive themselves within the larger circle of society.

Still – among actual climate scientists – this concerns just a small but politically vocal minority. Most of the names have been mentioned already.

May 27, 2011 at 23:15

There are plenty of emeriti around who have not lost their marbles, but by and large they have no appetite for the fray.

This is a wonderful discussion, with lots to think about, particularly the entrenched-ego connection. It was an amazing feat to get this amount of agreement from that group.

One huge problem is that people who think this through can see that addressing our urgent problems will require an almost unbearable sacrifice of living standards, while the advertising/industrial/infotainment nexus is busy trying to get us to buy more products all the time. I notice now we are supposed to use disposable everything for fear of not being clean and socially acceptable. The production of status symbols and things to waste is a huge industry. Most people feel they “deserve” more, not less, no matter they are relatively well off or not.

I’m reading something OT, but feel this Clarence Darrow quote is worth it:

“battle for human liberty, a battle that was commenced when the tyranny and oppression of man first caused him to impose upon his fellows and which will not end so long as the children of one father shall be compelled to toil to support the children of another in luxury and ease” (New Yorker 5/23/11)

Problem is, some identify the IPCC and attempt to get recognition of the real dangers of climate change are part of a scheme to impose world government, and don’t see that in fact this liberty they desire is part and parcel of the need for a massive effort by all humans on the globe to share better. An attempt to return to 19th century conditions, where 1% controlled 51% of the wealth (they only have 35% of it now) is framed as liberty, instead of the common need for clean water, shelter, and enough to survive on without hardship.

May 28, 2011 at 00:17

Bob Brand:

Yes, that seems one of the common patterns.

This offers a catalog of possible explanations for climate anti-science, although many are not specific to that. This is from p.13-14 of CCC.

In that catalog are:

PSY2 Contrarian nature; even without attention

PSY3 Contrarian attention: gets much more attention/publicity; may help career

PSY6 High-bar, low-bar: real science takes work; contrarian, easy acceptance

TEC1 Long Anchor: early position, held long , ~Type II error)

TEC2 Field non-science: evidence stays weak, mild ~Type I error

TEC3 Field pseudo-science: wrong: strongly disproved, strong ~Type I error

The PSY cases might apply to anyone, the TEC ones apply more to people in the field or nearby.

May 28, 2011 at 11:20

Susan,

I don’t think it necessary to “sacrifice our living standards”; that is actually a statement that plays directly into the hands of the do-nothing crowd. Using less energy in total and more renewable energy as part of that doesn’t necessarily equate to decreasing our standard of living, definitely not when stard of living includes non-monetary things such as health, happiness etc.

May 28, 2011 at 15:55

Hi John,

I’ve taken a look at your classification of denialist motivations (‘reasons’) and it does seem to be quite complete. The reasons I’ve encountered most often, in decreasing order of occurance, seem to be:

PSY7

IDE2

PSY2

FIN5

POL2

PSY5

PSY7 is illustrated by the idea of some ‘sceptics’ that climate science would claim CO2 is the sole driver of climate and climate change. They state that temperature should have exactly 100% correlation with CO2 levels.

When I try to explain there are many forcings, both positive and negative and on different time-scales, they say: “Well, why don’t these politicians and environmentalists say so!”, “So it is NOT all down to CO2, see, I was right after all!”

Then i take a very deep breath, count to ten, and I try to explain that at least climate scientists and the IPCC have never claimed it is… Of course, they never actually read the WGI reports. But then I run into PSY7 where they say: “Well, there are multiple causes so HOW ON EARTH can anyone ever predict what the climate will do!”

So then I am down to explaining how the effects of multiple variables can be distinguished because they all vary in time and we can look at the effect of perturbations, such as volcanos and solar cycles, and they just can’t comprehend that such a ‘complex’ analysis can ever work – while it is obviously a very common thing in technology and science. PSY7 definitely seems to be a big one – monocausality as an ethical belief about nature and concerning human ‘guilt’.

Off-topic sidenote to John Mashey: I’ve had the pleasure of using a number of your R3000 and R10000 machines at SARA/NIKHEF and at AT&T Labs in Amsterdam, in the late nineties and early 2000’s. Among these were the big boys TERAS and Aster (an Altix system). Hats off to you, Sir.

May 28, 2011 at 16:44

Bart, thanks for the correction. I failed to say what I really meant, and you’re right it’s a tricky area. I will have to be more careful and think it through.

It is, however, not possible to continue on our expanding consumption model with an expanding population. A little time with network TV and in some superstores shows that we have come to equate standard of living with things and appearances. You are absolutely right that satisfaction and contentment run much deeper and if people would embrace true value and overcome industry’s push against change we could manage quite nicely.

Meanwhile, I found John Mashey’s chart particularly useful. Thanks.

May 28, 2011 at 16:46

Oops, perhaps “manage quite nicely” is also sloppy. At this point everyone needs to pitch in with a few rough patches along the way. But manage, certainly, with a little wisdom and hard work. I take heart from humanity’s tendency to step up in a crisis.